© 2014-

Challenging the state monopolies (1)

Over the years many state broadcasting systems became stale and insular, reluctant to experiment and slow to develop new programmes or services to meet the changing tastes of their listeners. Why should they try? They had a complete monopoly position with no worries about the output of competitors who may steal their audience. In many countries, particularly European ones, there was a latent demand amongst advertisers and listeners for alternative radio services, but before these could be provided loopholes in the various national and international regulations had to be identified.

In places with a state monopoly system such as Britain there simply was no opportunity for an entrepreneur to legally establish a private, commercially funded radio station broadcasting from within the country on a frequency which had been allocated to it by international agreement. Therefore, to put a station on the air within the limitations of the law, prospective operators were forced to look elsewhere for a base from which they could legitimately broadcast.

One loophole in the rules and regulations was identified by enterprising British commercial broadcasters before the Second World War when the transmitters of various European stations were hired and used to beam programmes to audiences eager for a more varied and lively output than the BBC was offering at the time, especially on Sundays.

The first attempt at providing such an alternative to the fledgling BBC came in 1925 when the transmitter of Radio Paris was used to present an English language fashion programme sponsored by Selfridges, the London department store. Unfortunately due to the absence of almost any advance publicity for the programme the French station only received three letters from listeners saying they had heard the broadcast!

saying they had heard the broadcast!

Unsuccessful in audience terms it may have been, but this broadcast was to set a precedent for the future. The Radio Paris programme, and the sponsorship deal with Selfridges, had been arranged by Captain Leonard F Plugge, who having learnt from this experience re-

Other entrepreneurs tried too. In 1927 Hilversum Radio in The Netherlands broadcast a series of Sunday Concerts, sponsored by radio manufacturers Kolster Brandes Ltd., which were directed at listeners in Britain, while Radio Toulouse started English language broadcasts in 1929 with programmes sponsored by various British gramophone companies.

By the beginning of the 1930s Captain Plugge was back on the scene. A former consulting engineer on the London Underground, he was at that time running a business organising some of the earliest holiday package tours to France and his vehicle was equipped with one of the first ever car radios, manufactured by Philco. He realised as he toured France tuning in to various regional stations that they could be a possible outlet for further broadcasts to British audiences.

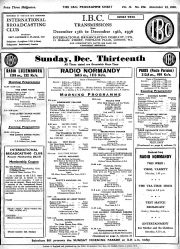

By 1930 five million radio sets had been sold in Britain and in May of that year, ha ving learned many lessons from his initial experiences a few years earlier, Captain Plugge decided to form the International Broadcasting Company (IBC) and exploit this large potential audience. He managed to negotiate a deal with Fernand le Grand, head of the radio station at the Benedictine distillery at Fecamp in northern France, to hire airtime from

ving learned many lessons from his initial experiences a few years earlier, Captain Plugge decided to form the International Broadcasting Company (IBC) and exploit this large potential audience. He managed to negotiate a deal with Fernand le Grand, head of the radio station at the Benedictine distillery at Fecamp in northern France, to hire airtime from his experimental station broadcasting under the call sign Radio Normandy.

his experimental station broadcasting under the call sign Radio Normandy.

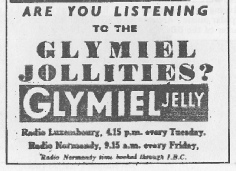

The IBC started its transmissions in October 1931 using the Fecamp transmitter on a wavelength of 269.5m. The broadcasts were initially transmitted at a power of 10Kw but this was later boosted to 20Kw when a new transmitter was installed at Louvetot in Normandy. Consequently the programmes were able to be received over a large part of southern England and the station soon attracted a large listenership.

The first employee of IBC and the station's first 'Disc Jockey' was Max Stanniforth who presented a three hour programme consisting largely of popular contemporary dance music. The station even invented the 'IBC Orchestra', leading listeners to believe that it could provide stiff competition for the BBC, which by then had its own range of successfully established orchestras. Although no such orchestra actually existed at IBC it served to give the distinct impression that the whole operation was  much larger than it was in reality.

much larger than it was in reality.

The International Broadcasting Company also later used the transmitters of other Euro pean stations to beam programmes to Britain -

pean stations to beam programmes to Britain -

- Poste Parisien on 312.8m with a power of 60Kw

- Radio Lyons on 215m with a power of 25Kw

- Radio Toulouse on 328.6m

- Radio Mediterranne on 235.1m

- EAQ Madrid on 30m shortwave

- Radio Cote d’Azure on 240m

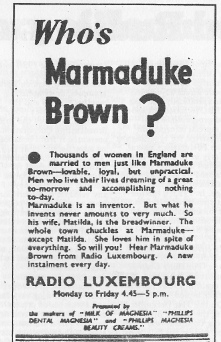

By the end of 1932 twenty one British advertisers were sponsoring English language programmes on European radio stations, including producers of cigarettes, foodstuffs, record and radio equipment and cars as well as film companies and various retail distributors. Advertising expenditure by British companies on these stations was estimated to be in the region of £400,000 per year in 1935 and by 1938 this figure had increased to £1.7 million, a very significant sum in those days.

Captain Leonard Plugge

Click image to enlarge

Radio Normandy jingle, 1930s

Ground

Floor

Back to

State Monopolies and International Agreements

Back to Gallery index

Fernand le Grand

Challenging the State Monopolies (2)

Click images to enlarge